“Hey, look what I found,” said my coworker, thrusting a postcard-sized piece of something in my face.

It was a week or two before Christmas, and all the fake trees our company ran around installing at local businesses during the lead up to the holidays were out already. Despite that, there was still a gaggle of older models in various states of disrepair that sat unused throughout the warehouse, where everything lived in the off season.

“What is it?”

“Not sure,” they said, holding out the card for me to take. “I found it in one of the Christmas trees. It’s got a soldier on it. You’re a veteran, so we thought you might know…”

I accepted the proffered card and began examining it. My associate only offered a quick shrug, and then they were gone as if they’d never been there in the first place. Obviously, the actual answer was not a top priority of theirs. Fine by me.

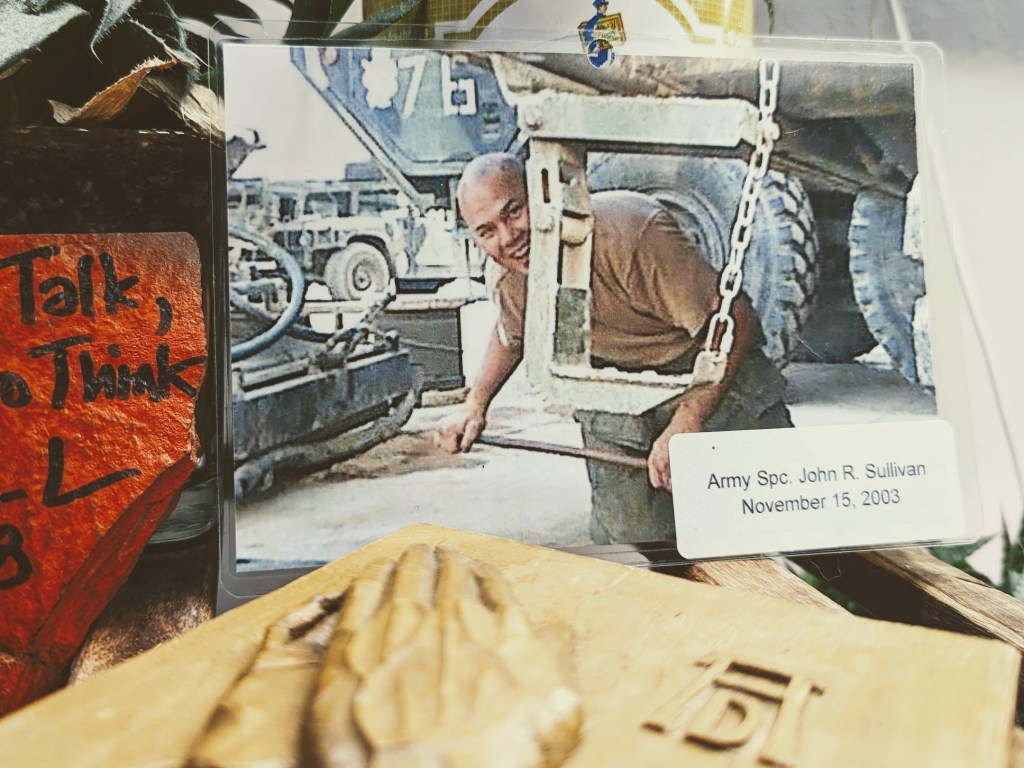

On one side of the laminated 4×6 photo was a picture of an Army soldier, crew cut, holding a large tool and smiling brightly at the camera as he works on a vehicle. He looks somehow happy, almost carefree even. Like this is his calling, that moment his rasion d’etre. This was no doubt a good memory.

On the bottom right it says, “Army Specialist John R. Sullivan, November 15, 2003.”

20 years ago…

I flip the photo.

The back side is printed repeatedly with “Kodak Moments” in ghost-gray script. Another bit of text in the bottom right, this time with his name and another year, 2019.

I eased back into my chair, staring at the photo, taking my time and soaking in details like the woodland camo painted Humvee in the background, or the number “76” painted on the side of another, larger piece of machinery beside him.

Him…

Specialist John R. Sullivan…

—

Specialist Sullivan had been a mechanic assigned to the 626th Forward Support Battalion, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

On November 15, 2003, he died tragically when the Black Hawk helicopter he was in collided with another over Mosul, Iraq, likely due to a rocket-propelled grenade. A Bronze Star and a Purple Heart were given to his widow. A widow who had just given birth to two-month-old twin boys whom Sullivan would never get to meet in person…

See, the thing about the guy is that he’s got a goddamn infectious smile in the photo. Unforced. The real deal. With expressive eyes.

It haunts me. I can’t get it out of my head after I first see it, so I stare at it more, trying to figure out why. After a long moment, I finally get it—he looks just like so many of my friends from the military. All of us, young, dumb assholes after 9/11. Gung ho. Full of energy and, dare I say, a smug American optimism. Maybe I’m projecting, but the guy in the picture— “Sully” to those who knew him—could have been any of us.

It was an eerie feeling. I was looking at a deceased soldier who had randomly made his way into my life through a series of chaos-theory-level convergences to remind me that lots of us my age didn’t make it back…and that even more who did, only made it back physically. It was like looking at a ghost, like when I used to do military funerals. Call it a memento mori.

I never had to go anywhere dangerous in my seven years in the Navy, unless you count certain parts of Chicago. That also means I didn’t lose anyone close to me on active duty for that reason, either. Thanks to the swipe of a pen and a smiling liar, I got to spend my seven years in the Navy stateside. I was lucky, though at the time I didn’t think so. My blood was up from 9/11, and at 21-years-old I wanted something akin to some good ol’ American style shock and awe. What I got was orders of magnitude less exciting, but overall, much, much safer.

What I know at this point, after having spent time dealing with my own PTSD issues and meeting a lot of other veterans doing the same, is that physical injuries weren’t the only things that people came back with from over there. And the non-physical injuries are just as debilitating.

What’s more, many of my current veteran friends talk about their traumas not in terms of what they brought home with them, but rather what they left behind in those places. The buddies. The memories. The parts of themselves that got left to rot in the wastes of Iraq or were forgotten in the peaks of Afghanistan and never made it back again.

In the next breath, many will also tell me that they wish they could go back, that it doesn’t feel right here for some reason anymore. That they’re anachronisms, out of place in space and time, clashing violently with the current era.

Mental gymnastics aside, here in the big unknown of late 2023, Iraq is only questionably stable, and Afghanistan belongs once again to the Taliban.

I think: What the fuck was all this for in the first place?

—

Not to canonize the man, but by the accounts left on online memorials, Sullivan was one hell of a guy, one we’d have all been better off for knowing.

I like those types of people.

After leaving the Army at the end of his first enlistment, he and his wife moved from Washington State back to Illinois, near his hometown of Countryside. Eventually, after struggling to find work and with twins on the way, he reenlisted in May 2003. Less than two months later, he was back in Iraq.

He played in a local rock band in Tacoma, Washington and was a respected musician in the scene. The type of guy who eventually got a guitar shipped into Iraq so he could keep playing. A guitar that was, like the man, ultimately lost in the accident. A tribute concert was held in his honor the next year, with each performer honoring him and the proceeds going to his widow.

Shortly before his death, he sent his wife two dozen roses for her birthday and the birth of their sons. Even though he would never meet his boys in person, his wife was able to send some sound recordings to him in Iraq and he was able to see them both briefly, one time, on webcam.

On his “Fallen Heroes Memorial” page (an online memorial for service members lost in Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom), put up in early 2004, there are one hundred or so entries. People he knew from both his enlistments leave their own personal notes. His Commanding Officer offers condolences, and his musician friends speak of the things he taught them on the guitar.

An old bandmate waxes philosophical over how much Sullivan had left to accomplish—that he reenlisted to support his family and paid the ultimate price, then thanks him for it.

It’s rough. It should be.

But the most heartbreaking entries come from his father, James. They are generally short, but there are many. Almost as many as all the others. Beginning in 2004, they continue for years, eventually petering out somewhere after mid-2013. Well after the tribute concerts and funerals.

Even when there were years of time when no one else posted, Sullivan’s dad is there letting his boy know that he still loves him, still misses him. That he won’t be so quick to let his memory fade into the ether. A feeling that I know well if only for my own reasons.

I can’t help but tear up as I read entry after entry, many nothing more than “I love you. I miss you. Dad.” This is a man steeped in boiling hot pain and admiration, riding the passage of time and grief like a great cosmic surfer hoping to straddle the line between love and loss, and somehow find closure without ever forgetting. To lessen the pain, but never the memory.

The entries become too hard to read, reminding me of something my own father would do.

My head swims and I look away…

—

What does it really mean to keep a memory alive? Only certain memories make their way into the firmament of collective human records. Writers, specifically historians, have a bit of an unfair advantage in this aspect as much of what is kept alive through millennia happens to rely heavily on their work. Next might be philosophers or scientists, etc.

But only certain things, certain concepts, people, or memories, make it through the ages intact. Things as important as family are forgotten within a few generations, simply as a matter of course. I, for example, have no real concept of my great-grandparents beyond a name. I could look them up, but at some point, there will be fewer and fewer of us to look them up until one day, there will be no one left to remember them at all.

This sounds grim, but it’s simply the way this works. Entire galaxies have been created and destroyed throughout the span of billions of years, going quietly into the deep black with no fanfare and nothing to carry on their memory. We’re certainly no different, and we certainly can’t stop it. One day soon, all of us will be star stuff, whether we like it or not.

So why even keep memories alive in the first place?

This is a complicated topic for me. In the Navy, one of my collateral duties as a young sailor was honor guard, a fancy name for the folks who do the military funerals we’ve all seen in movies. We did other funerals wherever needed in North Texas, but the main focus was on the week-long duty rotation at the Dallas-Fort Worth National Cemetery. The weeks we were assigned to the duty rotation could vary in intensity, but during busy times we did multiple funerals a day, some days with little time to rest in between.

One of the hardest parts for me of performing a military funeral honor was always presenting the flag to the next of kin. After the part of the ceremony where the flag is folded up into a blue triangle with white stars, it still must be given to the family member. These folks, in my experience, ran the gamut—everyone from moms to bikers to kids. It could have been anyone. And they almost all cried.

To present the flag, you have to do a few things. First, you get down on one knee and look the next of kin in the eye. Next you give The Speech where you, on behalf of the President, thank them for their loved one’s years of faithful service to a grateful nation. Then you can hand them the flag.

The hardest part was always looking them in the eyes and giving them The Speech. I felt fake saying the words and hated that part, but it was looking them in the eyes that always got me.

I didn’t figure it out until my last funeral…

When I presented the flag to my grandmother on that day at Tahoma National Cemetery outside Seattle, reflected at me was the picture of a woman who needed this closure. Someone who had lived a long life and deserved this speech and this flag and this memory. It wouldn’t bring our family member back, and it wouldn’t make the hurt any less. But this memory would be etched into my grandmother’s mind and would offer her a sort of comfort in the way thinking about my grandfather’s military funeral did for me. It would be bittersweet, but closure often is.

This is why we keep a memory alive despite the inexorable march of time.

It’s the look in each person’s eye when I presented the flag. It’s the closure my grandmother got. It’s the relatives. It’s the friends. It’s the children and grandchildren and coworkers that these people touched. It’s the impact they had or the smile they flashed or the guitar lessons they gave.

It’s because marble fades and bone decays.

It’s because, well, fuck time.

It may get us all in the end, but sometimes it’s right to struggle against the inevitable. And keeping the memories of our loved ones alive is a worthy fight.

—

After my coworker had left, and I had finished staring at the laminated picture of Specialist Sullivan, I thought about what I should do with it.

I wasn’t going to throw it away. I didn’t know anyone who knew him or who would want it, and it wasn’t going back into the fake Christmas trees.

Truth be told, the second he landed on my desk, I felt like there was a reason that he’d made his to me over all those years. I’m not sure what it was, or why, but maybe his memory needed to make it into the hands of another veteran, one who had some experience with the dead, just to be remembered a bit longer. Maybe he needed closure of his own. Maybe this is all bullshit I’ve made up in my head, too.

As I contemplated the fate of the photo, I thought of my own veteran friends. About the friends they’d lost. About the cost of those lost, and about the funerals and the crying next of kin. Then I thought about what I would want if it were me in that picture.

After some time, I got up from my desk. My chair back creaked as it returned to vertical, and I put my hands on my hips, twisting side to side to stretch. Reaching for the photo, I walked the few feet to the end of my desk, near a window where an old, beautiful fiddle leaf fig tree lives.

Over the years, I’ve put various ornaments on the tree in homage to our company’s goofy secondary holiday revenue stream. Under the careful shading of the wide, flat leaves that make up the canopy, the soft white glow of a string of Christmas lights illuminates the ornaments, making them glow in faint red and silver hues.

I move some of the silver balls to the right, one of the reds down and to the left.

I take the postcard and place it in the middle of the tree, twisting the wire on top to make sure it doesn’t come off.

For a year, I walk by the photo every day at work.

One day, not long before Christmas, I take the photo down and slip it in my bag. When I get home, I take it out. Holding it for a few long seconds, I examine it again, thinking of the voyage that this person’s memory took to get to me. Who put the photo in the tree back in 2019? What type of stellar coincidence had it taken for this situation to even happen? My mind runs.

Then I look at the shadowbox that holds my grandfather’s military medals from WWII and Korea, and those from my great uncle from the same period. I see the old black and white photos of my grandmother and her sister during World War II on top of the bookshelf. I think of my favorite photo of me and my three closest veteran buddies, the filthy animals, now years old and getting older…

I walk over to a large shelf in my dining room packed with various plants, pictures, and mementos.

On one shelf, near eye level, is a fist-sized piece of shale, spray-painted orange, with a handwritten message on it from a firefighter mentor I used to work with. In front, on the same shelf, is a wooden carving of the famous Praying Hands by Albrecht Dürer. Above and below that shelf are pictures of my family, dating back to the 1800s.

I move a plant aside, a rock to a different shelf.

Tenderly, next to the spray-painted message from my mentor, I stand the photo of Army Specialist John R. Sullivan up, leaning it against a couple of old, tired lace aloes.

Finally home.

Another memory that I’m happy to keep alive.

Leave a comment